By Elizabeth Farrelly, Sydney Morning Herald, 18 February, 2016

Okay. So, premise. Poor people are not just failed rich people. And our presumption that they are is as cliched and reductivist as the (mono)-culture it produces.

The poor – defined here as those in need of housing help – are critical city players, and not just as economy-fodder. We tend to see poverty as a sign of moral or intellectual deficit but, in truth, poor people might equally be defined as those with goals other than money, those who care more about singing or saving people than hedge-funds or negative gearing.

In this way, poor people are broadeners and deepeners – complicators, if you will – of the urban headspace. Which is why public housing matters, and not only to them, but to you.

When Packer’s casino is built, 70 glittering storeys on a glittering harbor, it is unlikely to house a couple of dozen penniless local artists among the Lear-jet set. But it could, and if Sydney were a healthier, wiser and more confident city, it would.

It’s orthodox to regard cities as fragile ecosystems, where intervention is therefore perilous. And it’s orthodox to see poverty as a canker within this, to be frowned upon, excised, cauterised. But in truth, only monoculture cities are fragile, like monoculture grasslands. A diverse, interdependent city draws resilience from its very complexity. Public housing is a means of guarding this complexity.

This – as much as altruism – is why wise cities require a percentage of public housing in new developments. It’s what’s known as “inclusionary zoning” and in cities like London it applies across the board. Here, the Baird government’s promise to “ensure large redevelopments target a 70:30 ratio of private to social housing” is only a “target” and applies only to private redevelopment of public land.

NSW has a massive 60,000 households on the social-housing wait-list. The Baird government’s much-vaunted “new era of public housing” – and the promised $2 billion construction boom it wears like a monkey on its back – will deliver just over a third of this, or 23,000 homes, over 10 years.

But they compensate in enthusiasm. As we speak, developers are bidding on the first tranche of 3000 social dwellings across six existing public-housing sites at Macquarie Park, Gosford, Tweed Heads, Seven Hills, Telopea and Liverpool.

Why so keen? Are developers the new philanthropists? Uh… no. There’s a sweetener, a big one. They get to build twice as many units again, for private sale, on public land. Essentially, it’s a swap: public flats in exchange for public land.

It’s not necessarily such a bad deal for the public. Mixing it up lessens the stigma, spreads the disadvantage and should improve design quality. But the public nature of both the land and the housing means that we – you and I – should care, a lot.

We should make demands. We should insist that the shaping of these developments is too important to be left (as usual) to developers. That the temptation to flog one inner-city block for five ex-urban ones is resisted; that these developments become beacons for the future; and that purpose-specific community housing not-for-profits are briefed this way.

Why does it matter that inner-cities give foothold to the poor? To see it properly, it’s useful to consider that usually neglected low-income stratum, artists. That the trickle of creatives leaving Sydney has lately become a minor torrent may seem trivial, but in fact goes to the heart of the urban question.

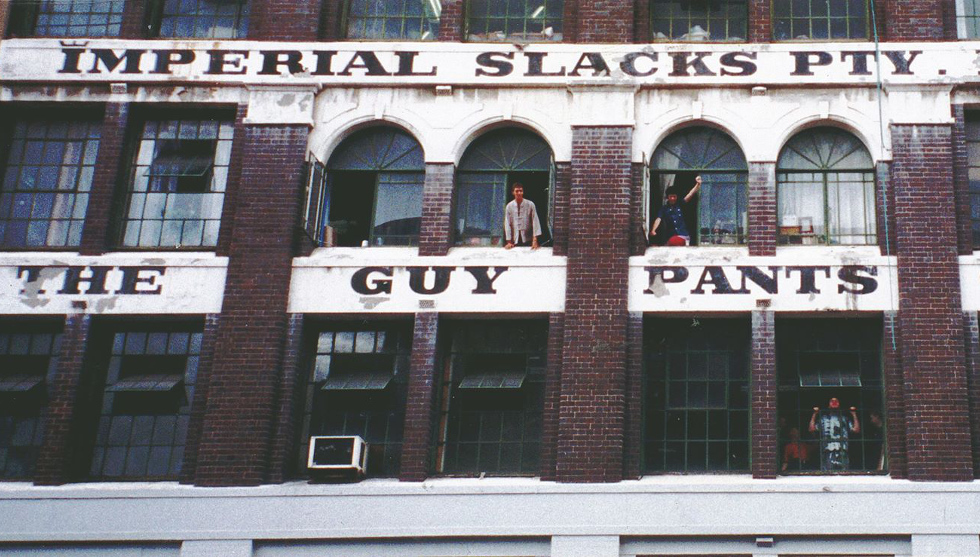

It is a little-known property-fact that artists are a reliable indicator species. All good cities have an artland, which is usually the last slum but one. Place Pigalle, Greenwich Village, Camden Lock; Paddo, Redfern, Erko, Marrickville; life-sustaining habitat for musos, writers, painters, potters, poets, rapsters and cabaret queens.

These colonies may be 10 years ahead of the value-curve, or 30, but they’re always ahead. Not because artists are prescient, getting in early to make a killing. Quite the contrary. Artists are ahead because that’s not even a factor in how they think. This means they’re (generally) poor, which forces creative change.

Typically the process is this. Artists, often young and usually just a heartbeat from dereliction, are first-wave colonisers, followed by architects, poets and musos and then, gradually, bars and cafes. Later, young fashionistas start bussing in from the burbs for the funky thrall. By the time, perhaps a decade on, their parents start to buy – so that former art-dives fetch more millions than they have storeys – the artland is long gone.

It’s an old pattern, this gentrification. But what’s different now is direction. For over a century the pull has been consistently inward, conditioning us to regard the link between creativity and density as inherent, an urban gravity. But now gravity is reversing. For the first time in over a century, creativity is heading out.

Sydney’s artland is no longer Surry Hills, Erko or even Marrickville’s warehouse district. Now, says art-world goss, the art-belt is defined by a two-hour radius from downtown; Gosford, Lithgow, Collector and the Gongs, Mitta and Wollon. This is where the arterati now seek the cutting edge.

You might think this sad but not shattering. We all struggle for foothold in the big city. Art is luxury, hardly the city’s core business. So we don’t owe its creators a living. Right?

Well, yes and no. The erasure of artists from the city demos should give us serious pause, and not only for the loss of core workers.

Artists bring a unique moral flavour to a city; not simply by making art but because, by definition, they have values other – let’s say higher – than money. They are the refiners of the fabric, the cumin and cinnamon in an otherwise less sophisticated stew, the weeds in a damaged landscape that, far from constituting damage, reveal then set about healing it.

And that’s why we should have inclusionary zoning. For our own sakes we should mandate poor people’s housing in all private development, most especially on public land. As it happens, Packer’s casino fits that bill perfectly.